7 minute read:

I’m disabled. I have been for a number of years, but not many people are aware of it. For one thing, I don’t have a lot of people in my orbit; a handful of good friends whom we left behind when we moved out to the sticks, a spouse and a son, and about a dozen doctors, PAs, therapists, etc. Aside from cashiers, pharmacists, and gas station attendants I don’t interact with a whole lot of people. And when I do, it’s a treat as I’m mostly home alone six days a week. When I’m around others, I’m usually chipper and friendly despite being in pain and living in a fog.

This is where things get dark… and a little sexist.

In the world I live in, women are expected to make others (generally, men) comfortable. I’ve been trained, starting when I was a teenager, to not disrupt the genteel existences of the few adults around me. So I quietly internalized having been abused. My guardian—my uncle—made it clear (without actually saying the words, of course) that he didn’t intend to deal with what my mother’s estranged husband had done. As a teenager, I had strong opinions about what I’d been through, and in response, my uncle expelled me from his home, washed his hands of me. I learned at 15 not to make men uncomfortable.

Maybe we shouldn’t be comfortable with the way those in power treat those who are vulnerable?

I want to pause and acknowledge I’m obviously writing from the cis-gender perspective. The movement to recognize that human gender is more complex than a simple binary breakdown is another conversation for another time, and one I support with enthusiastic hopefulness. I’m no expert on gender fluidity, or really anything, but it seems a number of societal problems could be relieved by not pigeonholing people into a rigid and limited system of self-identification. But, again, that’s a whole ‘nuther conversation. I’m a cis-woman, that’s where I write from.

Moving on… For a while there, health insurance was hard to come by for a lot of Americans. I needed it and didn’t have it for a decade, so I masked through the pain to work so I could hopefully earn it. And I still mask, as a survival strategy. Animals do it, too. They mask so other animals don’t kill them. I masked so I could be employed.

The effect of this was that I was usually dissociated from my own body—which had its pros and cons.

Pro: I could get a temporary placebo effect from pretending everything was okay, but it was temporary (con). Pain serves a purpose. It’s there to tell you to stop and tend to the problem. I was telling my body to shut up and wait its turn, and it shouted back, “Fuck you! Pay attention to me, now… or else!”

I’ve been living in the “Or else!” stage since the early 2010s. And today, the Social Security Administration is asking me to demonstrate how hurt I’ve been, and for how long.

Now I have to experience my body and learn how to live in the torturous truth.

I’m still afraid of making people uncomfortable. I tend to apologize for being sick. One of my doctors is wonderful about it. She’s a good egg. I’m lucky to have her. She’s the one who finally figured out that I have Ankylosing Spondylitis. But I’m careful with the others—especially the men. When men are uncomfortable, generally they disengage. Apparently many of them can’t help it, I guess it’s a human weakness. So I read the room.

I want, I desire, to live in the dark, torturous truth.

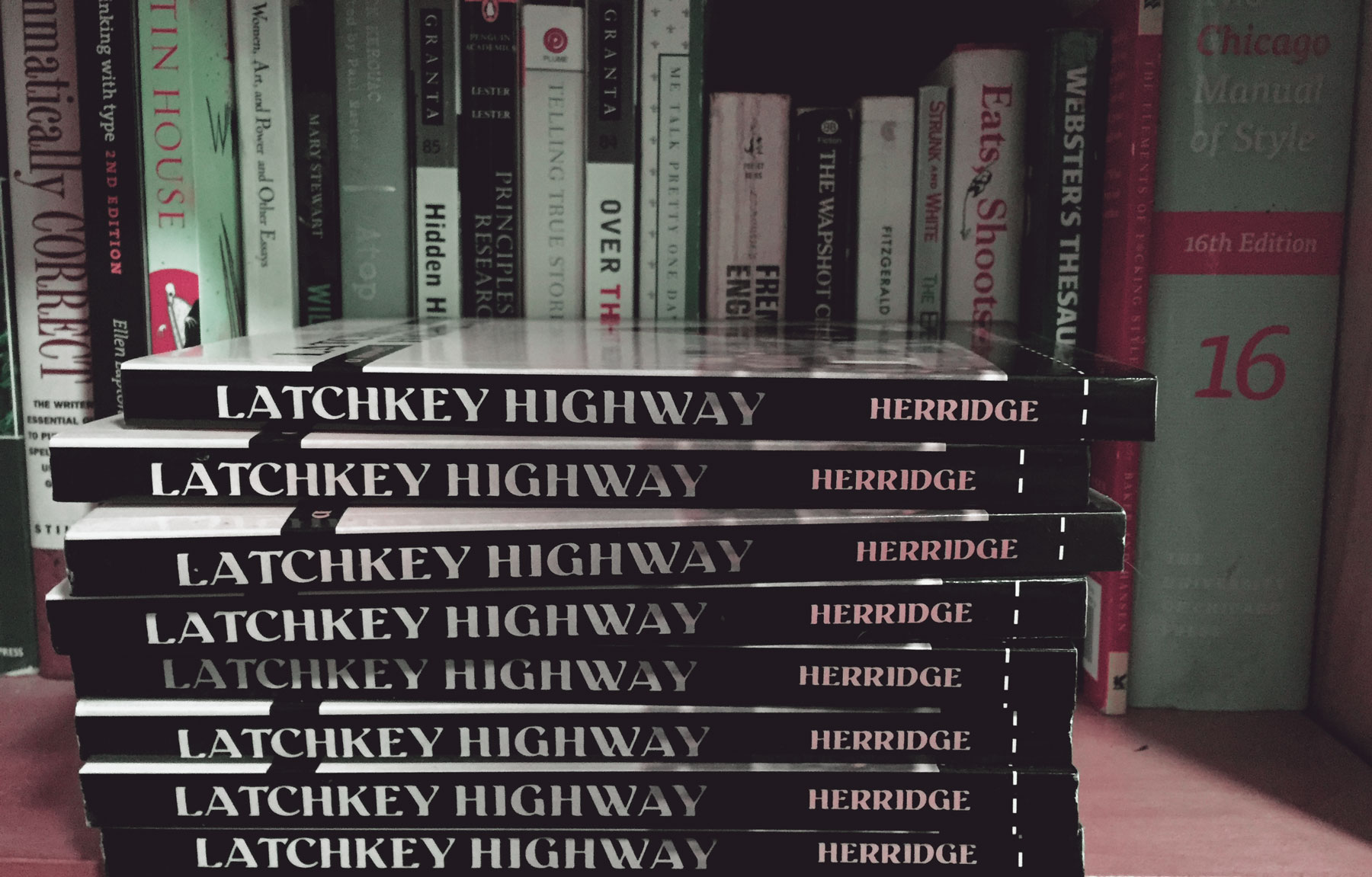

I want to learn how to live there; I will be pissed if that superpower was ‘nurtured’ out of me by adults who were really shitty at adulting. I need to occupy that pit, to hang brocade curtains and burn scented candles there. I will make that pit my homely home full of books, dog toys, and home-baked bread, since those adults failed to provide one for me. I will live out my days in my comfy-cozy pit of despair, and not sugar coat a damn thing for anyone.